Sometimes the universe seems to be nudging you in a particular direction. As a Buddhist I tend to ignore ideas of ‘fate’ – karma, yes, but that’s a different subject. Sometimes, though, you feel yourself being edged along a path that isn’t, perhaps, the one you would have chosen yourself. It’s hard to ignore a really good coincidence.

Sometimes the universe seems to be nudging you in a particular direction. As a Buddhist I tend to ignore ideas of ‘fate’ – karma, yes, but that’s a different subject. Sometimes, though, you feel yourself being edged along a path that isn’t, perhaps, the one you would have chosen yourself. It’s hard to ignore a really good coincidence.

My novel about Filippo Lippi and his early life in Florence, The Painter of Souls, has just been published. I’ve just finished writing another novel. So I’m in that slightly Purgatorial space between books, suspended between the solid familiar ground of actual work. Sniffing the wind for my next subject. I’ve been wanting to step away from Renaissance Italy and write about the 20th Century, but I’m not sure the universe agrees.

A couple of days ago I had to write a small – microscopic, really – travel piece about Florence. Initially I wanted to write about the Ponte Vecchio, contrasting its modern incarnation with what it had been like in the 15th Century, but it turned out that the subject had to be more tourist and less imagination. Still, I had started thinking about the bridge and its past. These days it’s essentially a glamorous rat-run, channeling tourists back and forth over the Arno p ast the jewellers and and goldsmiths that are the bridge’s traditional occupants. It wasn’t always like that – of course it wasn’t. History wouldn’t be history if there wasn’t a bit of nastiness hiding behind any given veneer of civilisation. And the Ponte Vecchio must have been pretty nasty. In the 15th Century, it was the place where Florentines went to buy meat. Butchers had been there for a long time, and in 1442 the city gave all the shops over to the Guild of Butchers until the end of the 1500s, when things had grown so disgusting that the city replaced them with the goldsmiths, who were cleaner and payed a lot more rent.

ast the jewellers and and goldsmiths that are the bridge’s traditional occupants. It wasn’t always like that – of course it wasn’t. History wouldn’t be history if there wasn’t a bit of nastiness hiding behind any given veneer of civilisation. And the Ponte Vecchio must have been pretty nasty. In the 15th Century, it was the place where Florentines went to buy meat. Butchers had been there for a long time, and in 1442 the city gave all the shops over to the Guild of Butchers until the end of the 1500s, when things had grown so disgusting that the city replaced them with the goldsmiths, who were cleaner and payed a lot more rent.

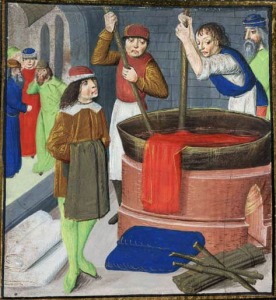

It isn’t all that hard to imagine a hot Tuscan summer day on the bridge: the shouts of the butchers, the thud of cleavers, the clouds of flies, the splash and slap of guts, bones and rind being thrown into the river. The water running under the arches was already pretty disgusting, mind you. Two of the industries that underpinned the wealth of Florence – cloth dyeing and leather tanning – were thriving just upstream. Tanning leather on an industrial scale used to require (as it still does in countries without stringent pollution laws) industrial quantities of faeces – preferably dog but certainly human as well – and dyeing used urine to fix certain colours, especially the reds for which Florence was famous. The river must have been thick with tanning effluent and streaked with dye.  This probably wouldn’t have mattered all that much in the winter. The Arno is a mountain stream and runs deep and fast. But when it ran low in the summer, the smell would have been eye-watering. Still, you would have stood looking downstream, watching the fishermen who were netting carp, eels, perch, all of which would have been set out for sale in the fish market near the northern end of the bridge. Filippo Lippi’s father was a butcher, and the artist, as young boy, would have been very familiar with these sights and smells.

This probably wouldn’t have mattered all that much in the winter. The Arno is a mountain stream and runs deep and fast. But when it ran low in the summer, the smell would have been eye-watering. Still, you would have stood looking downstream, watching the fishermen who were netting carp, eels, perch, all of which would have been set out for sale in the fish market near the northern end of the bridge. Filippo Lippi’s father was a butcher, and the artist, as young boy, would have been very familiar with these sights and smells.

I had been imagining all this while writing my travel piece. A bit later, we were sitting down to dinner when the eldest daughter noticed that the Chef was wearing one of her favourite bracelets, a silver piece she had bought decades ago from a jewellers in Burlington, Vermont. I’ve seen her wear it many, many times over the years we’ve been together.  That evening, she had taken it off and the children were admiring it, pointing out the little sculpted figures on the interlocking panels: a lion, St George and his dragon, a winged cherub, a coat of arms and a fleur-de-lis. One of them noticed a mark on the back and I was summoned with my jeweller’s loup (which I found last year, bizarrely, on top of a Dartmoor tor). The mark just said ‘silver’ but then I saw that the fleur-de-lis isn’t the usual kind but has curlicues sprouting from between the petals. Not a French lily but a Florentine one. The coat of arms, on closer examination, has five balls arranged across the little shield. The arms of the Medici family. How could it have taken me 23 years to notice all this? A couple of minutes at the altar of Google told us that, yes, this was a piece of jewellery from Florence, made by Peruzzi Coppini, an ancient family of silversmiths who have been practicing their craft since 1510. They still have a shop in Florence and yes, it is on the Ponte Vecchio.

That evening, she had taken it off and the children were admiring it, pointing out the little sculpted figures on the interlocking panels: a lion, St George and his dragon, a winged cherub, a coat of arms and a fleur-de-lis. One of them noticed a mark on the back and I was summoned with my jeweller’s loup (which I found last year, bizarrely, on top of a Dartmoor tor). The mark just said ‘silver’ but then I saw that the fleur-de-lis isn’t the usual kind but has curlicues sprouting from between the petals. Not a French lily but a Florentine one. The coat of arms, on closer examination, has five balls arranged across the little shield. The arms of the Medici family. How could it have taken me 23 years to notice all this? A couple of minutes at the altar of Google told us that, yes, this was a piece of jewellery from Florence, made by Peruzzi Coppini, an ancient family of silversmiths who have been practicing their craft since 1510. They still have a shop in Florence and yes, it is on the Ponte Vecchio.

Yesterday we drove down to Kingsbridge, a pretty little town just south of where we live. As seems to be happening everywhere, the high street is being swallowed up by a rash of charity shops but in Kingsbridge, for some reason, these are unusually good and in Oxfam, staring at me from a glass case, was Jacob Burckardt’s The Altarpiece in Renaissance Italy. I bought it, obviously. There’s a lot of interesting stuff about Filippo Lippi in it, and the musings of a truly great historian about art and faith. The threads of a new idea might already be gathering: so much beauty here, so much richness, so many contradictions: piety, wealth, talent. Faith and money: mixed together, they might curdle into a tasty story. When the universe nudges you, it’s sensible not to resist too hard.

staring at me from a glass case, was Jacob Burckardt’s The Altarpiece in Renaissance Italy. I bought it, obviously. There’s a lot of interesting stuff about Filippo Lippi in it, and the musings of a truly great historian about art and faith. The threads of a new idea might already be gathering: so much beauty here, so much richness, so many contradictions: piety, wealth, talent. Faith and money: mixed together, they might curdle into a tasty story. When the universe nudges you, it’s sensible not to resist too hard.

Nice one pip I shall check it out tomorrow. Lots of love from the four of us.

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLiked by 1 person